Monday, December 29, 2008

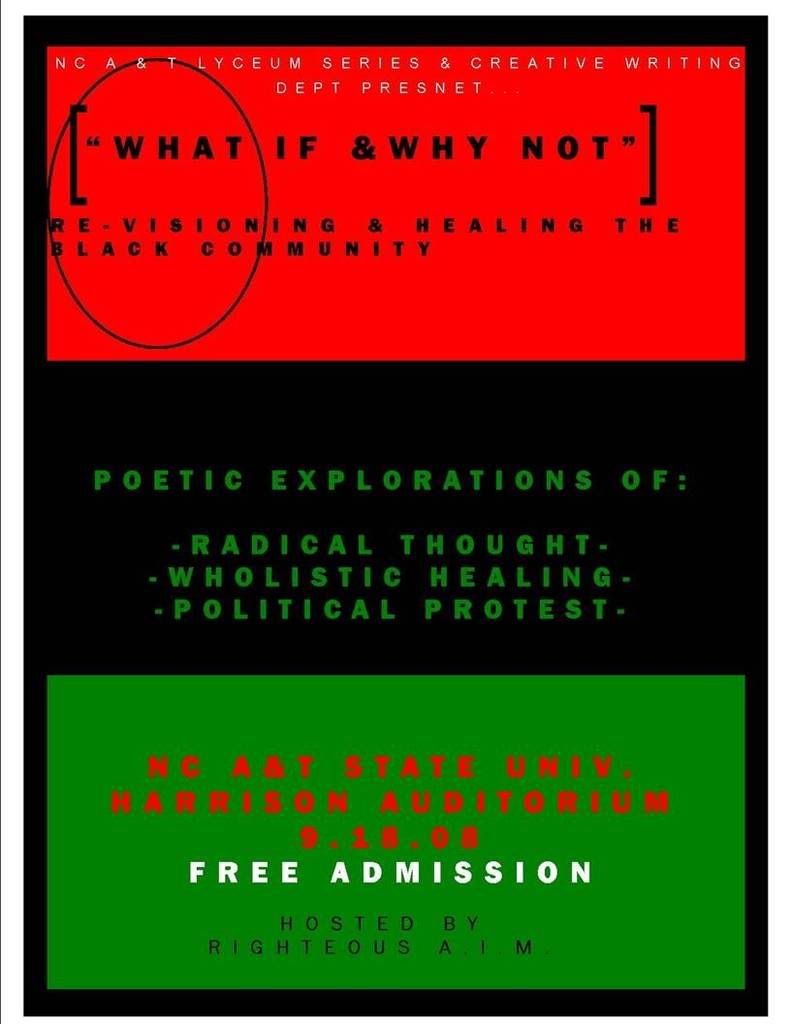

Monday, November 17, 2008

re/memories

21:40 - i hear you breathing for me/ an embodied blues for megan williams

after performing and meditating on the most recent installation of "i hear you breath for me/ an embodied blues for megan williams" i wrote this...

1. she thinks she sees waterblood

steps pores wide with fear

her whiteness like magnified imagination

"and there was fake blood and a woman cut herself"

her neck (re)shocked red as she turns the corner

her mother can see the whole black woman unsliced

left hand trembling

2. we are not a/part

we are not a/part wearenota/part wearenota / part we arenota/ part

even if my last name is not williams even if i tell the story you choose to forget

even if the dollars come as drops instead of pours even if you dream a piece of

fabric is a brick wall even if i bang silence like a steel drum even if you wear

white male privlege like a badge of honor even if i make you remember what

you choose to forget even if the story incites a thick mucus to grow in the back

of your throat even if

3. when we hold fear like a lover and fold our tears into envelops that craddle our screams we pretend our necks are full of jazz and scorpio thunder we pretend our open parts are a diary of cinnamon sundays we pretend a shout is a shower of blessings we pretend plump hairs relaxed thin do not hold stories of our mothers and our mothers' mothers we pretend we can bury ourselves in books and lecutres and conferences and "study"

we pretend it is apart of our genetic makeup to be numb we pretend we can bury ourselves in good dick and good feelings and good wine and good deeds

we pretend it is apart of our genetic makeup to be bottomless we pretend we can bury ourselves in the blindness of never more we pretend we have paralized tonsils we pretend flesh does not burn and that we have forgotten how to decode black girl pain like it is not an opera written in our skin/tone

4. tattle tell tit your tongue will be slit and every little boy in town will have a little bit

- mama audre lorde

5. and the line i forgot...

mary had a little lamb little lamb little lamb

mary had a little lamb whose fleece was whiiiiiii whhhhhhhhhhhh whhhhhhhhhhhi

whhhiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii wwwwwwwwwwwwwwwww whiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiite as snow

-remixed nursery rhyme

6. after we wrap ourselves like a cacoon we are a dictionary of backs and fingers and southern sea sways we infuse our beating bodies into a blank space we are not mourning but recharging and thanking ourselves for continuing the journey

7. the brothers pray approach slowly contemplate some revolutionary shit pray request hugs dance their frustration dance their honesty about not knowing what to do i am thankful for the stillness of their eyes and how they listen with their palms

Monday, October 27, 2008

October 27, 2008

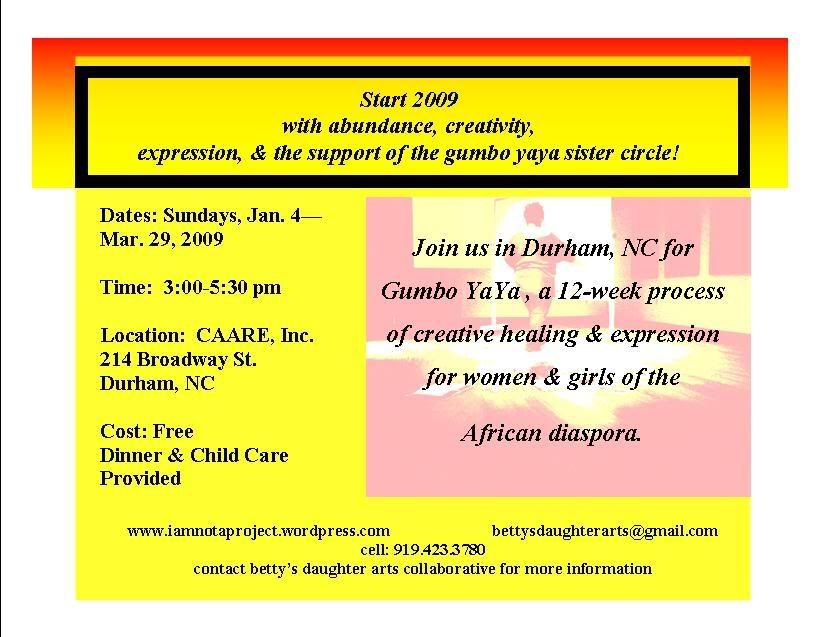

Gumbo YaYa/ or this is why we speak in tongues travels~~~~south!

It is that time, again. Last year Gumbo YaYa/ or this is why we speak in tongues worked magic in NYC. Almost a year to date, I sent out this email to women for support of this so fresh and so necessary improvisational, sista-circle, healing, performance opportunity.

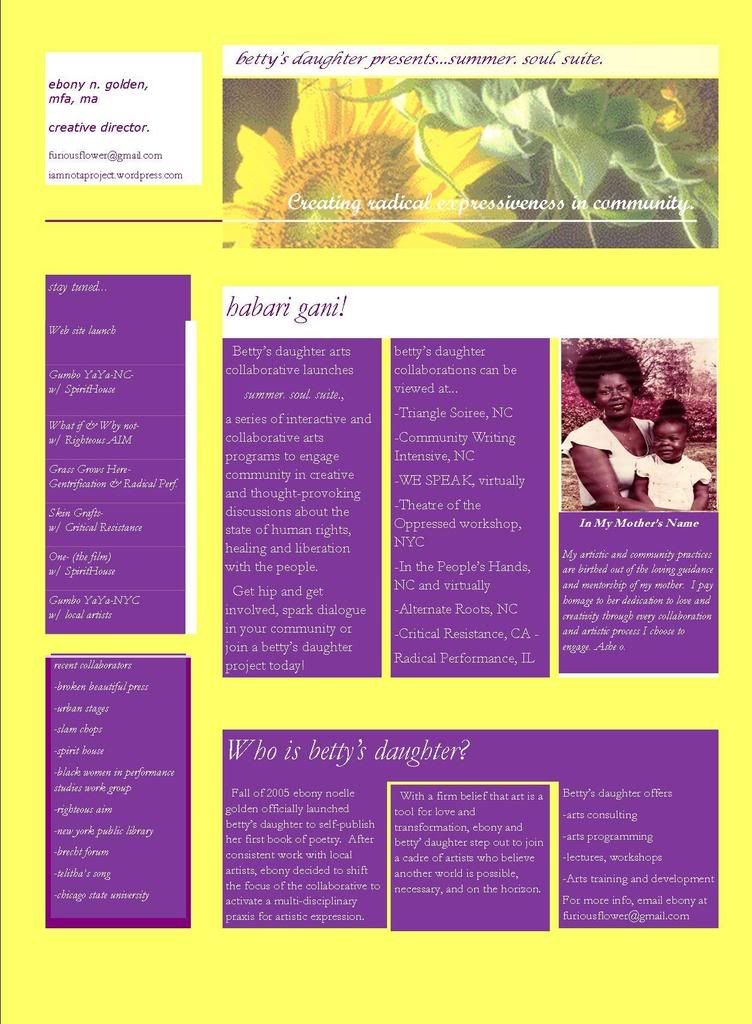

I am Ebony Golden currently living in Manhattan and working as an arts consultant and performer. Over the last year, I had the wonderful pleasure of working with a beautiful group of women who helped me think through what Womanist Performance Methodology and Practice is about. I had the opportunity to study with, learn from, and make trouble with some of the flyest sistas around. We honored ourselves. We were able to be honest. And we participated as we could. I would not have graduated without them.

I add these sistas to my infinitely growing family of sistas around the country. I am so blessed to work and dream with you all. Thank you Ayanna, Geneva, Joi, Cammile, Chelsea, RonAmber, Crystal, Tonya, Samantha, and everyone else who participated along with the rest of my family in DC, TX, GA, NC, IL CA, LA, and in other spaces. You hold me up, thank you.

It is time to begin the 2nd cycle of Gumbo YaYa! Through the generous funding and support of SpiritHouse-NC, North Carolina Humanities Council, Healing with CAARE the 2nd cycle will happen in Durham, NC.

I am dedicated to my healing, the healing of the women in my family and extended family, and the world. This is a process we are creating everywhere, let's continue to tap in together and see what shifts.

This process will have a few opportunities for performance, live and virtual, but mostly I am interested in articulating a poetics of womanist performance process and methodology that can be reproduced by us every where to heal ourselves and this world.

NEED

1- Intern interested in arts management, performance, grassroots activism, media relations, and social justice. Applicant must be flexible, a self-starter, and dependable. Applicant must be based in Durham-NC (or close by). Course credit and possible stipend available.

NEED

Women and girls to participate. If you know of a school, community center, or pre-existing program who might be interested in collaborating, let me know.

NEED

I need you to tell our story. A small group of sistas who are not afraid to undertake this work with me, whether they understand exactly where it is headed or not. Sistas who enjoy movement, music, writing, photography, people, good food, performing, making a fuss about us (black women), and who are not afraid to say we (black women) matter anywhere in this world.

NEEDS

1. sistas to perform several times during a 12-week period and beyond

2. videographer/ photographer/ editor

3. choreographer

4. stage manager

5. 'zine designer

6. web designer

NEEDS

1. voice recorders, tapes

2. gift cards (Target would be excellent)

3. performance space

4. video recorders, tapes, dvd

5. money, frequent flyer miles, train tickets, gas cards!!!

did I say money? oh, and money!

NEEDS

Your stories. Some of you are far away from me right now. But I would love to interview you about you and your healing process. Let's set up some time for phone interviews. I travel often, and maybe we can get together and talk.

Every one is invited to NC in March 09 to see a pivotal step in this journey. Can't wait.

Please take a look at the updated web site and leave poems, videos, letters, and words of encouragement on the Poetic Healing page.

Please do not hesitate to contact me with any questions.

Cool Spirits and Calm Waters,

--

Ebony N. Golden, MFA, American University

Performance Studies MA, NYU

Gumbo Yaya/or this is why we speak in tongues

Creative Director

www.iamnotaproject.wordpress.com

Thursday, September 04, 2008

Saturday, August 16, 2008

Wednesday, July 09, 2008

Tuesday, June 17, 2008

Sunday, May 25, 2008

acutonics or/ mic check one two one two/ a poem in praise of my mama

One time fo the sho shot!!!

two times for the bass!!!!

three time for the treble!!!!

and fo time the race!!!!!

1.

auuuuuuuuuuuuuum

auuuuuuuuuuuuum

auuuuum

aum

shanti

shantiiiiii

shantiiiiiiiii

aum

aum

aum

peace

my introduction to sound theraphy came through gospel music. i joined our youth church choir at brentwood baptist church as a teenager. i remember feeling so full of life, enegry, fullness whenever we began to sing praise music. i felt like a fully present member of a community. resounding proclaiming professing my love for the creator.

scratch that

my introduction to the healing aspects of sound came as a girl growing up in my mother's house. saturdays were sacred. ripe with mama daughter check ing, good breakfasts, and cleaning. lots of cleaning against a backdrop of herbie hancock, earth wind and fire, marvin gaye, fleetwood mac, quincy jones, teddy pendergrass and many others. my mom would pop in an 8-track and crank up the turn tables and we would clean and dance and enjoy each other in our home space.

scratch that

pre-school, yes pre-school. four years old. i study at a the local pre school off 610. we are required to learn square dance. we dance and do-si-do and spin our partners and promenade and all that jazz. wow how stereotypically texan is this. although i love to dance, even at four, i was even more drawn to the sounds. i remember feeling like i was moving in and through the sound. looking and thinking back now, i think i felt there was another place on the other side of the sounds coming from the harmonica, guitar, banjo and such. i felt i could travel through sound like it travelled through me.

i still feel this is true.

but

scratch that

i want to remember what i heard in my mamas belly. i know now that the sound of her voice is one of the many ways i am linked to this amazing woman. i have always been able to tell her emotional state from the sound of her voice. the intonation her pronunciation of my name EEEEEEEEEbony or Ebonyyyyyyyyyy or eBony all meant different things to me growing up and even now. i know this relationship to the sound of my mamas voice and sound in general predates even the twitch in my daddy's smile and the lilt in my mamas laugh that eventually created me, neverthess i meditate on originary enTrances to this aural affair.

2.

point of clarification

when i said scratch three times in the last section of this poem, i was not negating a narrative memory i was actually inviting multiple layers of time and narrative. see hip hop see jazz see toni morrison for more information. reference the dj as well how she piles time on top of sound to make a new now/present/moment. think about how the event is a thing and remembering the event is a new thing and remixing them both is entirely a new thing as well. see and reference the universe's cycles ebbs and flows. reference a conversation with mama dr. ahmad about astrology and cosmic cycles~~~~how the cosmic cycles happen on time and constantly in time but each time a cycles happens the universe is not the same, nor are the people experiencing and moving through the cycles.

3.

this is a poem about sound

this is a poem about sound

this is a poem about sound

this is a poem about sound

this is a poem about sound

this is a poem about sound

this is a poem about sound

this is a poem about sound

(rest)

4.

listen to erykah badus music. not the lyrics, well yes the lyrics but the music music music. listen to pings, dings, tones, hesis, mantras, noise, silences, flourishes, breaks, holes, holds, and more. watch her make music on stage. gadgets, mixers, orchestrations, (she breaks music with commands like "hold on" cause some moments need silence while others may need sonic layers). pay attention to the how her voice mimics not only instruments but sounds we can find in nature. reference birds, wind, trees, sun sets, internal harmony and discord. reference the recent pics of badu positioned with pitch forks reminds me of ancient egyptian healing rods. these rods were used to create atune the body using the energetic vibrations that could be absorbed aurally or directly by the affected organ. see http://www.egyptianhealingrods.com/IntroFrames.html. reference andre 3000/the love below and the mantra "vibrate/ vibrate higher".

this talk about mimicry and nature and pitch and sound in general transports me back in time to what i just wrote about how sound travels the body and how the body travels through sound. so badus sound and possible mirroring of natural sounds is a way to think about recovery and travel. she sings during the intro and outro "the world is gonna turn/ the world is on and on" which references a constant cycle motion fluidity that mirrors how sound travels. "the sun's movement does not bend to the will of humans". i wonder how sound can be interpolated into this system as well.

what i am saying is sound therapy is a method of recovering self, as the self shifts and moves and remixes. sound is a way of collapsing the supposed present/past/future because it is all just time and through sound we can access the selves we want to be we can tune the sufferring parts of our selves and we can highlight our strengths. check out khametic rituals using sound. check out your grand mama humming spirituals. check out a babies laugh. check out a clear day in new york city. check out the sound of your lovers breath. check yourself.

5.

this is a poem about the earth

this is a poem about the earth

this is a poem about the earth

this is a poem about the earth

this is a poem about the earth

this is a poem about the earth

this is a poem about the earth

6.

i am entering a space of intense silence and sound

i am entering a space of intense meditation and prayer

i am entering a space of stillness and motion

i am entering a space of communion and solitude

i am recapturing

recovering

reliving

remixing

layering

outlining

splicing

recouping

revolving

shifting

soul sonics

alining arits

absorbing yellow green and white light

swallowing brillance

and breathing up butterflies

7.

boom tik boom boom boom tik

boom tik boom boom boom tik

boom tik boom boom boom tik

"think twice think twice"

boom tik boom booom boom tik

boom tik boom boom boom tik

"back in the day now/ back in the day

when things were cool/ well well well/

all we needed was pa pa pa pa pa pa da

all we needed was pa pa pa pa pa pa da"

~~~~~~~~~~

check the healing rods the hands of the Pa-Hru (or king/queen language of ancient kemit. please note: the term pharoh is an inaccurate translations. reference my beloved elders, queen afua, and others who taught me this).

two times for the bass!!!!

three time for the treble!!!!

and fo time the race!!!!!

1.

auuuuuuuuuuuuuum

auuuuuuuuuuuuum

auuuuum

aum

shanti

shantiiiiii

shantiiiiiiiii

aum

aum

aum

peace

my introduction to sound theraphy came through gospel music. i joined our youth church choir at brentwood baptist church as a teenager. i remember feeling so full of life, enegry, fullness whenever we began to sing praise music. i felt like a fully present member of a community. resounding proclaiming professing my love for the creator.

scratch that

my introduction to the healing aspects of sound came as a girl growing up in my mother's house. saturdays were sacred. ripe with mama daughter check ing, good breakfasts, and cleaning. lots of cleaning against a backdrop of herbie hancock, earth wind and fire, marvin gaye, fleetwood mac, quincy jones, teddy pendergrass and many others. my mom would pop in an 8-track and crank up the turn tables and we would clean and dance and enjoy each other in our home space.

scratch that

pre-school, yes pre-school. four years old. i study at a the local pre school off 610. we are required to learn square dance. we dance and do-si-do and spin our partners and promenade and all that jazz. wow how stereotypically texan is this. although i love to dance, even at four, i was even more drawn to the sounds. i remember feeling like i was moving in and through the sound. looking and thinking back now, i think i felt there was another place on the other side of the sounds coming from the harmonica, guitar, banjo and such. i felt i could travel through sound like it travelled through me.

i still feel this is true.

but

scratch that

i want to remember what i heard in my mamas belly. i know now that the sound of her voice is one of the many ways i am linked to this amazing woman. i have always been able to tell her emotional state from the sound of her voice. the intonation her pronunciation of my name EEEEEEEEEbony or Ebonyyyyyyyyyy or eBony all meant different things to me growing up and even now. i know this relationship to the sound of my mamas voice and sound in general predates even the twitch in my daddy's smile and the lilt in my mamas laugh that eventually created me, neverthess i meditate on originary enTrances to this aural affair.

2.

point of clarification

when i said scratch three times in the last section of this poem, i was not negating a narrative memory i was actually inviting multiple layers of time and narrative. see hip hop see jazz see toni morrison for more information. reference the dj as well how she piles time on top of sound to make a new now/present/moment. think about how the event is a thing and remembering the event is a new thing and remixing them both is entirely a new thing as well. see and reference the universe's cycles ebbs and flows. reference a conversation with mama dr. ahmad about astrology and cosmic cycles~~~~how the cosmic cycles happen on time and constantly in time but each time a cycles happens the universe is not the same, nor are the people experiencing and moving through the cycles.

3.

this is a poem about sound

this is a poem about sound

this is a poem about sound

this is a poem about sound

this is a poem about sound

this is a poem about sound

this is a poem about sound

this is a poem about sound

(rest)

4.

listen to erykah badus music. not the lyrics, well yes the lyrics but the music music music. listen to pings, dings, tones, hesis, mantras, noise, silences, flourishes, breaks, holes, holds, and more. watch her make music on stage. gadgets, mixers, orchestrations, (she breaks music with commands like "hold on" cause some moments need silence while others may need sonic layers). pay attention to the how her voice mimics not only instruments but sounds we can find in nature. reference birds, wind, trees, sun sets, internal harmony and discord. reference the recent pics of badu positioned with pitch forks reminds me of ancient egyptian healing rods. these rods were used to create atune the body using the energetic vibrations that could be absorbed aurally or directly by the affected organ. see http://www.egyptianhealingrods.com/IntroFrames.html. reference andre 3000/the love below and the mantra "vibrate/ vibrate higher".

this talk about mimicry and nature and pitch and sound in general transports me back in time to what i just wrote about how sound travels the body and how the body travels through sound. so badus sound and possible mirroring of natural sounds is a way to think about recovery and travel. she sings during the intro and outro "the world is gonna turn/ the world is on and on" which references a constant cycle motion fluidity that mirrors how sound travels. "the sun's movement does not bend to the will of humans". i wonder how sound can be interpolated into this system as well.

what i am saying is sound therapy is a method of recovering self, as the self shifts and moves and remixes. sound is a way of collapsing the supposed present/past/future because it is all just time and through sound we can access the selves we want to be we can tune the sufferring parts of our selves and we can highlight our strengths. check out khametic rituals using sound. check out your grand mama humming spirituals. check out a babies laugh. check out a clear day in new york city. check out the sound of your lovers breath. check yourself.

5.

this is a poem about the earth

this is a poem about the earth

this is a poem about the earth

this is a poem about the earth

this is a poem about the earth

this is a poem about the earth

this is a poem about the earth

6.

i am entering a space of intense silence and sound

i am entering a space of intense meditation and prayer

i am entering a space of stillness and motion

i am entering a space of communion and solitude

i am recapturing

recovering

reliving

remixing

layering

outlining

splicing

recouping

revolving

shifting

soul sonics

alining arits

absorbing yellow green and white light

swallowing brillance

and breathing up butterflies

7.

boom tik boom boom boom tik

boom tik boom boom boom tik

boom tik boom boom boom tik

"think twice think twice"

boom tik boom booom boom tik

boom tik boom boom boom tik

"back in the day now/ back in the day

when things were cool/ well well well/

all we needed was pa pa pa pa pa pa da

all we needed was pa pa pa pa pa pa da"

~~~~~~~~~~

check the healing rods the hands of the Pa-Hru (or king/queen language of ancient kemit. please note: the term pharoh is an inaccurate translations. reference my beloved elders, queen afua, and others who taught me this).

Thursday, May 22, 2008

Women, Rock! and Politics Conference 2008

Institute for Women's Studies, UGA

Athens, Georgia

Everyone is welcome to this free conference. For information on local

accommodations, registration, and other details, go to http://www.uga.edu/iws/wrp08.html

Athens locals don't miss keynote performance by queer and feminist rock icon

Gretchen Phillips, 6pm Saturday

(http://www.queermusicheritage.us/aug2005.html) and after-conference party

with guest dj Melissa York.

Conference Program

Friday, May 30, Edge Hall, Hugh Hodgson School of Music, UGA

5:00 Opening reception

5:30 Welcome and Introductions

6:00 Fred Maus “52 Girls” A talk on the women of the B52s

7:00 Latin-American Scenes

Lesley Feracho , “Contesting the Nation :Women and Rock in Latin America”

Patricia Vergara “Funkeiras: Transgressing the Place of the Poor, Black, and

Female in Rio de Janeiro”

SATURDAY, May 31, Tasty World, downtown Athens

12:00 Brunch Buffet

1:00 Girls Rock Camps Collective, “Creativity, Community and Confidence

through Rock & Roll: Girls Rock Camps”

2:15 Rocking the Margins

Matt Jones, "(Re)discovering the Music of Judee Sill"

Sarah Cozort, “Women in Experimental Music”

3:00 Break

3:15 Stella Pace, “Riot Grrrl Self-Esteem Now: A Multimedia Performance”

4:00 Hip/Hop Feminisms

Ebony Noelle Golden, “Sonic Soul: Erykah Badu's Performance Practice”

Sarah Young Ngoh, “Black Motherhood in Hip/Hop and R&B Music”

Marnie Binfield, “Women’s Contributions to ‘Conscious Rap’”

5:45 Break

6:00 Keynote Performance/Presentation Gretchen Phillips

9:00- After-party at Tasty World with special DJ Melissa York, of The Butchies

midnite

UGA to host second annual conference on Women, Rock! and Politics

Athens, Ga.—The Institute for Women’s Studies at the University of Georgia is

hosting its second annual conference, Women, Rock and Politics, from Friday,

May 30 to Saturday, May 31.

This year’s conference brings together a great range of talks, images, and

performances on topics ranging from Girls Rock Camps, to hip hop feminism, to

the riot grrrl movement, to women in rock in Latin America.

The conference will begin on Friday at 5:00 p.m. with a reception and

presentations in Edge Hall at the Hugh Hodgson School of Music on the

University of Georgia campus, followed by a talk on the women of the B-52s by

renowned music scholar Fred Maus (UVA). Saturday's presentations and

performances, including keynote performance by rock icon Gretchen Phillips,

and conference after-party with guest dj Melissa York, will be at Tasty World in

downtown Athens. For a full program please visit www.uga.edu/iws.

The conference is free and open to the public. Edge Hall is located in the Hugh

Hodgson School of Music, Third Floor, at 250 River Rd on the eastside of

campus. Tasty World is located at 312 East Broad Street in downtown Athens,

Ga. For more information contact the Institute for Women’s Studies at 706-

542-2846.

Molly Moreland Myers

Public Relations Coordinator

Institute for Women's Studies

University of Georgia

706-542-0066 (voice)

706-542-0049 (fax)

momolly@uga.edu

Institute for Women's Studies, UGA

Athens, Georgia

Everyone is welcome to this free conference. For information on local

accommodations, registration, and other details, go to http://www.uga.edu/iws/wrp08.html

Athens locals don't miss keynote performance by queer and feminist rock icon

Gretchen Phillips, 6pm Saturday

(http://www.queermusicheritage.us/aug2005.html) and after-conference party

with guest dj Melissa York.

Conference Program

Friday, May 30, Edge Hall, Hugh Hodgson School of Music, UGA

5:00 Opening reception

5:30 Welcome and Introductions

6:00 Fred Maus “52 Girls” A talk on the women of the B52s

7:00 Latin-American Scenes

Lesley Feracho , “Contesting the Nation :Women and Rock in Latin America”

Patricia Vergara “Funkeiras: Transgressing the Place of the Poor, Black, and

Female in Rio de Janeiro”

SATURDAY, May 31, Tasty World, downtown Athens

12:00 Brunch Buffet

1:00 Girls Rock Camps Collective, “Creativity, Community and Confidence

through Rock & Roll: Girls Rock Camps”

2:15 Rocking the Margins

Matt Jones, "(Re)discovering the Music of Judee Sill"

Sarah Cozort, “Women in Experimental Music”

3:00 Break

3:15 Stella Pace, “Riot Grrrl Self-Esteem Now: A Multimedia Performance”

4:00 Hip/Hop Feminisms

Ebony Noelle Golden, “Sonic Soul: Erykah Badu's Performance Practice”

Sarah Young Ngoh, “Black Motherhood in Hip/Hop and R&B Music”

Marnie Binfield, “Women’s Contributions to ‘Conscious Rap’”

5:45 Break

6:00 Keynote Performance/Presentation Gretchen Phillips

9:00- After-party at Tasty World with special DJ Melissa York, of The Butchies

midnite

UGA to host second annual conference on Women, Rock! and Politics

Athens, Ga.—The Institute for Women’s Studies at the University of Georgia is

hosting its second annual conference, Women, Rock and Politics, from Friday,

May 30 to Saturday, May 31.

This year’s conference brings together a great range of talks, images, and

performances on topics ranging from Girls Rock Camps, to hip hop feminism, to

the riot grrrl movement, to women in rock in Latin America.

The conference will begin on Friday at 5:00 p.m. with a reception and

presentations in Edge Hall at the Hugh Hodgson School of Music on the

University of Georgia campus, followed by a talk on the women of the B-52s by

renowned music scholar Fred Maus (UVA). Saturday's presentations and

performances, including keynote performance by rock icon Gretchen Phillips,

and conference after-party with guest dj Melissa York, will be at Tasty World in

downtown Athens. For a full program please visit www.uga.edu/iws.

The conference is free and open to the public. Edge Hall is located in the Hugh

Hodgson School of Music, Third Floor, at 250 River Rd on the eastside of

campus. Tasty World is located at 312 East Broad Street in downtown Athens,

Ga. For more information contact the Institute for Women’s Studies at 706-

542-2846.

Molly Moreland Myers

Public Relations Coordinator

Institute for Women's Studies

University of Georgia

706-542-0066 (voice)

706-542-0049 (fax)

momolly@uga.edu

Thursday, May 08, 2008

Envisioning An Artist's Manifesta

Gumbo ya ya/ or this is why we speak in tongues:

Documenting Womanist Performance Methodology

iamnotaproject.wordpress.com

Envisioning an Artist’s Manifesta

Ebony Noelle Golden

I am the daughter of Pearl Glover, Bertha Sims, and Betty Sims. I am a Black woman who calls Houston, TX and Shreveport, LA home. I am a poet who writes and lives a poetic sensibility. I have many mamas, aunts, sistas, and nieces. Billie Sims, Shellie Sims, Dorothy Sims, Linda Sims, Cheryl McKnight, Nelma Hicks, Heather Hicks, Jayla Dancey, Joi Dancey, Jayna Dancey are some of the women and girl-children who inform who I am today. This manifesta is for them. Ashe o!

Culture

I guess that waltzes

Do not move me.

I have no sympathy

For symphonies.

I guess I hummed the blues too early

And spent too many midnights

Out wailing to the rain.

-Assata Shakur

In “The Quilt: Towards a twenty-first black feminist ethnography” Meida McNeal asserts, “The concept of diaspora in relation to Africa has undergone radical definitional shifts. Across these shifts in the use of diaspora as process, product, space and identity, the tropes of ‘African-ness’ and ‘blackness’ have been under constant negation, not solely on theoretical terrain but in actual embodied practice,” (60). I am intrigued and disoriented by the polyvalent nature of Blackness. This disorientation grounds me in an ongoing process that thinks about the violent nature of translation as a learned, expected and constantly re-imagined behavior in Black women’s daily experiences. As I engage language translation, I translate my body and my spirit. As I interact with others, I switch codes, “pass”, rub against identities that are not quite my own. The violent act of self-translation insists I ask, who’s language resides in my mouth? I struggle to locate myself in the ideas swirling around in my head. The indoctrination of the academy, the work of popular media outlets, the social fabric of this society all vie for space inside my body, and often win out over the desires, ideas, projects and processes that reside within the intimate space of my interior.

Is it possible to understand notions of Black womanhood in terms of the construction of language or “metalanguage”? Homi K. Bhabha reminds us, “The linguistic difference that informs any cultural performance is dramatized in the common semiotic account of the disjuncture between the subject of a proposition (enonce) and the subject of enunciation, which is not represented in the statement but which is the acknowledgement of its discursive embeddedness and address, its cultural positionality, its reference to a present time and a specific space” (270). With this in mind, I recognize my desire to write myself into a space, write space onto my body or write over/through the gap or “disjuncture”/disjunction/break that seems to separate Black women from the rest of the world. Writing can be a set of practices and actions that reconnect the self to the self, intimate and global communities.

The failure to write/act across the gap is one of the major failures of the women’s liberation or white feminist movement. In “African-American Women’s History and the Metalanguage of Race” Evelyn Higginbotham quotes Elizabeth Spelman’s claim that, “White feminists typically discern two separate identities for black women, the racial and the gender, and conclude that the gender identity of black women is the same as their own: “In other words, the womanness underneath the black woman’s skin is a white woman’s and deep down inside the Latina woman is an Anglo woman waiting to burst through” (6). Additionally, bell hooks describes the failure of feminist coalition building between Black and white women. hooks states, “One reason white women active in the feminist movement were unwilling to confront racism was their arrogant assumption that their call for Sisterhood was a non-racist gesture. Many white women have said to me, “we wanted black women and other non-white women to join the movement,” totally unaware of their perception that they somehow “own” the movement, that they are the “hosts” inviting us as “guests” (53). I ask myself: what is the skin under my skin? What is the voice within my voice? This vacuum that theoretically separates the blackness from womanness, self from self, is the void I speak of/over/through. I need to know, quite literally, what are the societal and gravitational forces displacing me from myself?

I am a refugee in my own skin.

Higginbotham’s article thinks about race as language. She writes, “Race serves as a “global sign,” a “metalanguage,” since it speaks about and lends meaning to a host of terms and expressions, to myriad aspects of life that would otherwise fall outside the referential domain of race” (5). In the case of Black women, one must consider what signifies us historically and contemporarily. What are the markers, traces, utterances that signal Black womanness? Hostense Spillers begins her essay “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book” with the following declaration, “Let’s face it. I am a marked woman, but not everybody knows my name. ‘Peaches’ and ‘Brown Sugar,’ ‘Sapphire’ and ‘Earth Mother,’ ‘Aunty,’ ‘Granny,’ ‘God’s ‘Holy Fool,’ a ‘Miss Ebony First,’ or ‘Black Woman at the Podium’ ” (65). Again words miss the gap. They contain instead of explicate who I am. There, in the definition, is another fissure I must leap across/out of the boundness of a commodified identity into the space of expansiveness. I find redemption in rejecting the “liminal” notions an constructions Black womanhood.

I speak her name

Mother

Mama

Mawu

Mawulisa

Ala

Jezanna

Songi

Mboze

Yemanja

Mbaba Mwana Waresa

Chi-Wara

Attempting to stretch my body across the gulf, stretching towards myself, stretching myself through translation is more than a kinesthetic or alchemic performance. It requires a seismic shift in the way the social constructs the intimate and the global constructs the individual. I agree with Renee Alexander Craft who believes, “African/black women have all too often been imagined, defined, labeled and packaged in ways that are at odds with who we are and understand ourselves to be” (56). The disjuncture is significant. This is why I am fixated on the sets of practices and the nuanced lexicon of Black women’s experiences. Not to limit our identity, but instead to bathe in the layered textures of our diversity. The representations and definitions are limiting, hurtful and sometimes backwards. Moreover, the definitions and representations are transmitted as truth largely by people who do not speak the same language I speak.

I am gravitating and maneuvering to the center of the universe. In order to transport myself through language and performance I first must start here, center stage. I want to stretch myself beyond the aforementioned terms. I am “Mother” but my identity, as Spillers insists, does not rest or begin with who or what I produce, rear or suckle. I speak across gulfs of legacy, trauma, kinship, futurity, expectancy, culture, body, space, and time to be seen or recognized by certain institutions or institutional representatives; but more so, to be recognized by myself. The issue of invisibility, or speaking oneself visible, resonates like the reverberating sound of a Buddhists’ singing bowl. Recently, I have begun to think about language as a set of ideas and actions in terms of the phenomenon of glossolalia, roughly translated as “speaking in tongues”.

This concept has been helpful in thinking about ideas and actions that speak to how specific individuals or communities linguistically and performatively engage with others. Amiri Baraka, in all his flawed brilliance and beauty, writes in Blues People “The spirits do not descend without music”. His ideas vocalize how spirit/soul/”re”memory/body are related to language and performance practices. I believe Black women are masters of glossolalic practices as we translate, not only the language the gods, the language of ourselves through our skins, actions and vocalizations.

Perhaps, Black womanhood is an avant-garde/experimental performance. Both the language, as I am writing and thinking about it, and Black womanhood push corporeal frontiers and urge ontological shifts in the manner in which human beings relate to sometimes hostile and other times lulling geographies. Blackness, as Adrian Piper, E. Patrick Johnson, and other notable scholars theorize, is just as slippery as the definitions of experimental/ avant-garde performance. Depending on where one is positioned or positions oneself on this stage called the globe, the United States, New York City, or some other space, Blackness looks and performs quite differently than one might assume.

E. Patrick Johnson teases out Blackness in Appropriating Blackness: Performance and the Politics of Authenticity. Johnson writes, “Blackness, too, is slippery—ever beyond the reach of one’s grasp. Once you think you have a hold on it, it transforms into something else and travels in another direction. Its elusiveness does not preclude one from trying to fix it, to pin it down, however—for the pursuit of authenticity is inevitably an emotional and moral one.” (2) Johnson explicates how blackness serves as a means to wiggle out of the crawl space or what Marcus Wallace refers to as the “scrawl” space of identity as it is constructed by genetic and social structures.

I experience and negotiate this world through this corporeal and affective reality. Black skin, Black sensibilities, Black acts conflate with the dominant discourses and hegemonies and make a real substantive relationship with myself and other Black women a job I work twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. Although current scholarship suggests we are possibly transitioning into a post-racial moment, I am still here writing visibility across gulfs. I cannot be evacuated from this skin or this legacy. I suggest that constructions of Black womanhood be expressed through the cultural practice of gumbo ya ya as theorized by Luisah Teish. She writes, “Gumbo ya ya is a creole term that means “Everybody talks at once,” It is stream of consciousness, it is argumentative, and it is loud! The person speaks comments on the subject at hand, any stories from the past and future probabilities that are seemingly relevant to the subject, the immediate environment, and their own inner process, all within the same unpunctuated paragraph. While the principal person is speaking, all other participants(who cannot truly be called “listeners”) are preparing what they’re going to say next (which cannot truly be called a ‘response’). The next person acquires “the floor” simply by cutting in and speaking louder than the present speaker. The new “floor master” is allowed a sentence or two and then gumbo ya ya starts up again” (139-140).

Gumbo ya ya, perhaps traces its genealogy back to the origins of the southern dish that bares the same name. Gumbo ya ya is a stew. Depending on the region, gumbo ya ya may contain different ingredients including shrimp, sausage, chicken, crab, and a myriad of vegetables. The main and most fundamental component of gumbo ya ya is the roux or what I call the soul of the dish. The roux is the gravy that holds all the ingredients together. Again, depending on one’s location the roux maybe either a tomato based gravy or a brown gravy made from the fat rendering of a piece of cooked meat. Gumbo ya ya features and highlights a menagerie of distinct and discernable flavors that collaborate to create an entire sensory experience.

Teish’s ideas about gumbo ya ya are similar to those theorized in “The Quilt” written by a collective of sista-scholars who matriculated through various degree programs at Northwestern University. The essay articulates theory and praxis for a contemporary and critical Black feminist ethnography. These notions of quilting, stitching together, stirring up all inform my current project, Gumbo ya ya/ or this is why we speak in tongues: Documenting Womanist Performance Methodology. Media McNeal unravels a series of questions that problematize process such as Gumbo ya ya/ or this is why we speak in tongues in “The Quilt”. She asks, “How do we – as scholars who are cultural workers – complicate debates about ownership, tradition, innovation and authority by tracking some bits of culture and eclipsing others? How does what we craft on paper and in performance intervene, making some small dent in established perceptions of what we thought we knew or what we ignored up until now” (73)? McNeal’s questions are indeed relevant and necessary in untangling such a complicated historical and contemporary narrative. Her questions also suggest that work must be done to hone methodological practices approaches to Black womanhood that critically and responsibly engage such issues that pertain to the “intimate histories” and cultural practices of Black women. Gumbo ya ya/ or this is why we speak in tongues desires to engage similar questions that further complicate scholarly and artistic engagement in and through Black womanhood.

Gumbo Yaya/ or this is why we speak in tongues is an artistic and spiritual work conceived by members of the Black Women in Performance Studies Work Group at New York University, under my facilitation and desire to spend a year in meditation of the issues articulated throughout this manifesta. Together we actualized Gumbo Yaya to highlight black women’s cultural production in relationship to community, self, legacy, spirituality and womanism. The piece was developed collaboratively over a six month period with women scholars and activists in New York City, Durham, NC, Atlanta, Georgia, and Houston, TX. Inter-generational narratives of spirituality and healing ground this creative and scholarly process, along with performances of healing and movement.

Gumbo Yaya/ or this is why we speak in tongues draws on the rich legacy of womanism as articulated by Chikwenye Okonjo Ogun-yemi and Alice Walker among others. Additionally, this process shapes and defines the practice of womanism as it performed presently by younger generations of black women. By galvanizing the energy of our foremothers, we intend to “make something new” as it is suggested through the artistic production and scholarship of Anna Deavere Smith.

Gumbo ya ya/ or this is why we speak in tongues works through Black women’s cultural practices as a means of highlighting the diverse experiences of the participants while enjoying experiences of solidarity and unity. This exploration critically engages notions of authenticity, authorship, voice, and expressivity as we question the agency and efficacy among us. We reclaim the legitimacy of our experiences and the power to narrate our stories as we live them in our own tongues and through our own language and practices.

i don’t wanna write

in english or spanish

i wanna sing make you dance

like the bata dance scream

twitch hips wit me cuz

i done forgot all abt words

aint got no definitions

i wanna whirl

with you

our whole body

wrapped like a ripe mango

- Ntozake Shange

Shange writes about the importance of nuanced articulation of identity in her essay “takin a solo/ a poetic possibility/ a poetic imperative”. Shange argues, “You never doubt bessie smith’s voice. I cd not say to you: that’s chaka khan singing ‘empty bed blues’. Not cuz chaka khan can’t sing empty bed blues/ but cuz bessie smith sound a certain way. Her way. If tina turner stood right here next to me & simply said ‘yes’…we wd all know/ no matter how much I love her/ no matter what kinda wig-hat I decide to wear/ my ‘yes’ will never be tina’s ‘yes’” (2). Ultimately the work of Gumbo ya ya/ or this is why we speak in tongues, in some ways, is exactly what Shange describes. The process provides a space for Black women rehydrate the flattened identities mapped onto or voices and bodies. The process provides a space through shared legacies through multiple tongues and movements that speak a communal truth.

Bibliography

Afua, Queen Sacred Woman. New York, NY: Random House, 2000.

Baraka, Amiri Blues People: Negro Music in White America. LeRoi Jones, 1963.

Collins, Patricia Hill Black Feminist Thought. New York, NY: Routledge, 2000.

Craft, Renee Alexander, McNeal, Meida, Mwangola, Mshai, Zabriskie, Queen Meccasia. “The

Quilt: Towards a twenty-first century black feminist ethnography”. Performance Research. Vol. 12. Issue 3. Sept. 2007. http://www.informaworld.com/openurl?genre=article&issn=1352-8165&volume=12&issue=3&spage=55.

Crenshaw, Kimberle. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist

Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.”

University of Chicago Legal Forum. 1989.

http://ezproxy.library.nyu.edu:2507/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/uchclf1989&id=1&size=2&collection=journals&index=journals/uchclf.

Ervin, Hazel Arnett. African American Literary Criticism. Twayne Publishers: New York, NY,

1999.

Hine, Darlene Clark, King, Wilma, Reed, Linda. Eds. “We Specialize in the WhollyImpossible:”

A Reader in Black Women’s History. Brooklyn, NY: Carlson Publishing, 1995.

hooks, bell. Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center. Boston, MA: South End Press, 1984.

Johnson, E. Patrick Appropriating Blackness: Performance and the Politics of Authenticity

Moten, Fred. “Taste Dissonance Flavor Escape: Preface for a solo by Miles Davis”

Women & Performance: a Journal of feminist theory, vol. 17, No. 2, July 2007, 217-246.

Piper, Adrian. Cornered. 1988. Google Video. 19 Apr. 2008.

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=-6756190809617046211&pr=goog-sl.

Piper, Adrian. Everything. Feb. 2008. Elizabeth Dee Gallery, New York. Apr. 2008.

Piper, Adrian. “Talking to Myself: The Autobiography of an Art Object.” Out of Order, Out of Sight: Volume 1: Selected Writings in Meta-Art 1968-1992. Cambridge, MA and London: The MIT Press, p 29-53.Piper,

Shakur, Asatta. Assata. Zed Light Books: Chicago, IL, 1987.

Shange, Ntozake. for colored girls who have considered suicide when the rainbow is enuf.

McMillian Publishing:New York, NY, 1977.

Shange, Ntozake. Nappy Edges. St. Martin’s Press: New York, NY, 1972.

Spillers, Hortense J. “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book.” Diacritics, Vol. 17, No. 2, Culture and Countermemory: The “American” Connection (Summer, 1987), pp. 65-81

Teish, Luisah. Jambalaya: The Natural Woman’s Book of Personal Charms and Practical Rituals.

Harper Collins: New York, NY, 1985.

Wade-Gayles, Gloria. My Soul is a Witness: African-American Women’s Spirituality. Beacon

Press: Boston, MA, 1995.

Walker, Alice. In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich: Orlando, FL,

1967.

Wallace, Marcus O. Constructing the black masculine; identity and ideality in African

American men’s literature and culture, 1775-1995. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002.

Saturday, May 03, 2008

thank you adrian piper for everything~~~Adrian Piper’s “Cornered” and “Everything”: Debunking Notions of the Post-Racial Moment

Adrian Piper’s “Cornered” and “Everything”: Debunking Notions of the Post-Racial Moment

(for New Orleans, Meghan Williams, Sean Bell, et. al)

Maybe, just possibly, blackness is an avant gard/experimental performance; just as performances that push corporeal frontiers or urge ontological shifts in the manner in which human beings relate to sometimes hostile and other times lulling geographies. Blackness, as Adrain Piper, E. Patrick Johnson, and other noted scholars theorize, is just as slippery as the definitions of experimental/ avant gard performance. Depending on where one is positioned or positions oneself on this stage called the globe, the United States, New York City, or some other space, Blackness looks and performs quite differently than one might assume.

E. Patrick Johnson teases out the complexities of this issue in his book Appropriating Blackness: Performance and the Politics of Authenticity. In the introduction, Johnson writes, “Blackness, too, is slippery—ever beyond the reach of one’s grasp. Once you think you have a hold on it, it transforms into something else and travels in another direction. Its elusiveness does not preclude one from trying to fix it, to pin it down, however—for the pursuit of authenticity is inevitably an emotional and moral one.” (2) Johnson reveal here how blackness serves as a means to wiggle out of the crawl space or what Marcus Wallace refers to as the “scrawl” space of identity as it is constructed by genetic and social structures.

While I am sure Blackness oscillates, wiggles, rewinds and “sidewinds” as Richard Schechner speaks of as a characteristic of performance, Blackness still is. I cringe at the thought of not being able to index at the site of collective and “intimate history”, joys, traumas, cultural practices and kinship Blackness. I am concerned about writers, thinkers and artists who assert we are in moving into a post-racial moment. Who decides this? Who is empowered to make such decisions? And what cost, if I choose to accept this thrust, do I pay not move pass this skin and this experience in this skin and these memories and these relationships to jump on the post –racial moment.

In “Cornered” Adrian Piper bursts the collective bubble of white and Black America. She reveals that most of us are Black. Furthermore, she suggests that Blackness is a dilemma. At first I was unnerved by this presumed assumption but soon she revealed what I interpreted as the real problem. The issue is what are our strategies for dealing with our collective Blackness? This, at first, I believed was directed solely at the white people watching the video, but Blackness is a genetic and social fact Black folks have to deal with as well. Piper proposes that white people should not assume everyone is white or that everyone wants to be white. Furthermore, she hints to the Black folks who may be watching that we should be doing something about this Blackness issue as well. We should be insisting, resisting, proclaiming and performing our Blackness no matter the social costs. For Piper, passing is not an option. The film concludes with an invocation—Welcome to the struggle, the “beautiful struggle” for wholeness and Blackness and voice.

May 2, 2008. I am still a little groggy from pulling an all-nighter. An organization called Creative Time is on Campus for the “Everything” project. The project centers around Piper’s most recent artistic work that was recently installed at Elizabeth Gallery. Creative Time is on campus painting “everything will be taken away” on people’s foreheads with henna paint. Barabara Pollack’s article “Adrian Piper, “Everything” includes an important quote about Pipers work. She quotes, “Once you have taken everything away from a man, he is no longer in your power. He is free. “ She adds, “This quote from Alexander Solzhenitsyn is the inspiration for Adrian Piper’s “Everything” series.” I planned to have my forehead painted, but nevertheless I slept instead.

I ventured to the gallery to see the exhibit. Having admired Piper’s work from afar it was a little disheveling seeing it so up-close and personal. Stark white walls and the ominous phrase disorient me. This is clearly about space, power, race in the Minimalist tradition she is known for. A hard to make out video of Meghan Williams are situated in one corner. The mirror watches, or reflects, me as I watch the video. I feel tugged and pulled as if Piper is standing here asking interrogating me in the calm and subdued voice she utilized in “Cornered”. She asks, “What are you going to do for Meghan?” My kinship with her, Piper and Williams, makes me even more ill-at-ease. I cannot make out her voice. I cannot make out my own.

I am not in a dark room with several chairs. I see a grid and dots, dancing a freaky choreography. The dots are connected by lines. I feel alone. Perhaps, the dots represent my relation to those around me. Again the Minimalist aesthetic employed by Piper, makes me feel the room is naked and that I am taking up a lot of space. These open spaces make me feel as if she intentionally left the room bare so that I can think, not so much about the art, but my relationship to it.

Piper’s work is about global positioning. It is about finger pointing. Although in “Cornered”, Piper says she does not mean to antagonize her audience I believe she does , and rightfully so. Everything has been taken away, and now even Blackness is being stolen by progressives, liberals, artists, scholars who choose not to deal with the messiness and presence of it.

Suggested Media and Readings

Sweet Honey in the Rock “We Who Believe in Freedom”

Johnson, E. Patrick, Appropriating Blackness: Performance and the Politics of Authenticity

www.elizabethdeegallery.com

www.adrainpiper.com

http://www.creativetime.org/programs/archive/2007/performance/piper.html

http://www.timeout.com/newyork/articles/art/27943/adrian-piper-everything

see "Cornered" posted to the blog

ebony noelle golden, mfa

furiousflower@gmail.com

Friday, May 02, 2008

Thursday, April 24, 2008

thank you adrian piper...for everything

Learn more about Adrian Piper at - www.adrianpiper.com

Dear Editor:

Please don’t call me a black artist.

Please don’t call me a black philosopher.

Please don’t call me an African American artist.

Please don’t call me an African American philosopher.

Please don’t call me a woman artist.

Please don’t call me a woman philosopher.

Please don’t call me a female artist.

Please don’t call me a female philosopher.

Please don’t call me a black woman artist.

Please don’t call me a black woman philosopher.

Please don’t call me an African American woman artist.

Please don’t call me an African American woman philosopher.

Please don’t call me a black female artist.

Please don’t call me a black female philosopher.

Please don’t call me an African American female artist.

Please don’t call me an African American female philosopher.

Please don’t call me a female black artist.

Please don’t call me a female black philosopher.

Please don’t call me a female African American artist.

Please don’t call me a female African American philosopher.

Please don’t call me an artist who happens to be black.

Please don’t call me a philosopher who happens to be black.

Please don’t call me an artist who happens to be African American.

Please don’t call me a philosopher who happens to be African American.

Please don’t call me an artist who happens to be a woman.

Please don’t call me a philosopher who happens to be a woman.

Please don’t call me an artist who happens to be female.

Please don’t call me a philosopher who happens to be female.

Please don’t call me an artist who happens to be black and a woman.

Please don’t call me a philosopher who happens to be black and a woman.

Please don’t call me an artist who happens to be a woman and black.

Please don’t call me a philosopher who happens to be a woman and black.

Please don’t call me an artist who happens to be African American and a woman.

Please don’t call me a philosopher who happens to be African American and a woman.

Please don’t call me an artist who happens to be a woman and African American.

Please don’t call me a philosopher who happens to be a woman and African American.

Please don’t call me an artist who happens to be black and female.

Please don’t call me a philosopher who happens to be black and female.

Please don’t call me an artist who happens to be female and black.

Please don’t call me a philosopher who happens to be female and black.

Please don’t call me an artist who happens to be African American and female.

Please don’t call me a philosopher who happens to be African American and female.

Please don’t call me an artist who happens to be female and African American.

Please don’t call me a philosopher who happens to be female and African American.

Please don’t call me a black artist and philosopher.

Please don’t call me a black philosopher and artist.

Please don’t call me an African American artist and philosopher.

Please don’t call me an African American philosopher and artist.

Please don’t call me a woman artist and philosopher.

Please don’t call me a woman philosopher and artist.

Please don’t call me a female artist and philosopher.

Please don’t call me a female philosopher and artist.

Please don’t call me a black woman artist and philosopher.

Please don’t call me a black woman philosopher and artist.

Please don’t call me an African American woman artist and philosopher.

Please don’t call me an African American woman philosopher and artist.

Please don’t call me a black female artist and philosopher.

Please don’t call me a black female philosopher and artist.

Please don’t call me an African American female artist and philosopher.

Please don’t call me an African American female philosopher and artist.

Please don’t call me a female black artist and philosopher.

Please don’t call me a female black philosopher and artist.

Please don’t call me a female African American artist and philosopher.

Please don’t call me a female African American philosopher and artist.

Please don’t call me an artist and philosopher who happens to be black.

Please don’t call me a philosopher and artist who happens to be black.

Please don’t call me an artist and philosopher who happens to be African American.

Please don’t call me a philosopher and artist who happens to be African American.

Please don’t call me an artist and philosopher who happens to be a woman.

Please don’t call me a philosopher and artist who happens to be a woman.

Please don’t call me an artist and philosopher who happens to be female.

Please don’t call me a philosopher and artist who happens to be female.

Please don’t call me an artist and philosopher who happens to be black and a woman.

Please don’t call me a philosopher and artist who happens to be black and a woman.

Please don’t call me an artist and philosopher who happens to be a woman and black.

Please don’t call me a philosopher and artist who happens to be a woman and black.

Please don’t call me an artist and philosopher who happens to be African American and a woman.

Please don’t call me a philosopher and artist who happens to be African American and a woman.

Please don’t call me an artist and philosopher who happens to be a woman and African American.

Please don’t call me a philosopher and artist who happens to be a woman and African American.

Please don’t call me an artist and philosopher who happens to be black and female.

Please don’t call me a philosopher and artist who happens to be black and female.

Please don’t call me an artist and philosopher who happens to be female and black.

Please don’t call me a philosopher and artist who happens to be female and black.

Please don’t call me an artist and philosopher who happens to be African American and female.

Please don’t call me a philosopher and artist who happens to be African American and female.

Please don’t call me an artist and philosopher who happens to be female and African American.

Please don’t call me a philosopher and artist who happens to be female and African American.

Dear Editor,

I hope you will bring to my attention any permutations I have overlooked.

I write to inform you that

I have earned the right to be called an artist.

I have earned the right to be called a philosopher.

I have earned the right to be called an artist and philosopher.

I have earned the right to be called a philosopher and artist.

I have earned the right to call myself anything I like.

Thank you in advance for your consideration.

Adrian Piper

1 January 2003

Saturday, April 05, 2008

blackness, art, politcs oh my!!!

By HOLLAND COTTER

Published: March 30, 2008

IN the 1970s the African-American artist Adrian Piper donned an Afro wig and a fake mustache and prowled the streets of various cities in the scowling, muttering guise of the Mythic Being, a performance-art version of a prevailing stereotype, the black male as a mugger, hustler, gangsta.

Skip to next paragraph

Enlarge This Image

Paul Fortin/Pope.L

The artist William Pope.L, on the cover of the catalog to his 2003 retrospective exhibition, “eRacism.” More Photos »

Multimedia

Slide Show

On Race and Art In the photographs that resulted you can see what she was up to. In an era when some politicians and much of the popular press seemed to be stoking racial fear, she was turning fear into farce — but serious, and disturbing, farce, intended to punch a hole in pervasive fictions while acknowledging their power.

Recently a new kind of Mythic Being arrived on the scene, the very opposite of the one Ms. Piper introduced some 30 years ago. He doesn’t mutter; he wears business suits; he smiles. He is by descent half black African, half white American. His name is Barack Obama.

On the rancorous subject of the country’s racial history he isn’t antagonistic; he speaks of reconciliation, of laying down arms, of moving on, of closure. He is presenting himself as a 21st-century postracial leader, with a vision of a color-blind, or color-embracing, world to come.

Campaigning politicians talk solutions; artists talk problems. Politics deals in goals and initiatives; art, or at least interesting art, in a language of doubt and nuance. This has always been true when the subject is race. And when it is, art is often ahead of the political news curve, and heading in a contrary direction.

In a recent solo debut at Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery in Chelsea a young artist named Rashid Johnson created a fictional secret society of African-American intellectuals, a cross between Mensa and the Masons. At first uplift seemed to be the theme. The installation was framed by a sculpture resembling giant cross hairs. Or was it a microscope lens, or a telescope’s? The interpretive choice was yours. So was the decision to stay or run. Here was art beyond old hot-button statements, steering clear of easy condemnations and endorsements. But are artists like Mr. Johnson making “black” art? Political art? Identity art? There are no answers, or at least no unambiguous ones.

Since Ms. Piper’s Mythical Being went stalking in the 1970s — a time when black militants and blaxploitation movies reveled in racial difference — artists have steadily challenged prevailing constructs about race.

As multiculturalism entered mainstream institutions in the 1980s, the black conceptualist David Hammons stayed outdoors, selling snowballs on a downtown Manhattan sidewalk. And when, in the 1990s, Robert Colescott was selected as the first African-American to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale, he brought paintings of figures with mismatched racial features and skin tones, political parables hard to parse.

At the turn of the present millennium, with the art market bubbling up and the vogue for identity politics on the wane, William Pope.L — the self-described “friendliest black artist in America” — belly-crawled his way up Broadway, the Great White Way, in a Superman outfit, and ate copies of The Wall Street Journal.

Today, as Mr. Obama pitches the hugely attractive prospect of a postracial society, artists have, as usual, already been there, surveyed the terrain and sent back skeptical, though hope-tinged, reports. And you can read those reports in art all around New York this spring, in retrospective surveys like “Wack! Art and the Feminist Revolution” currently at the P.S 1 Contemporary Art Center in Queens, in the up-to-the-minute sampler that is the 2008 Whitney Biennial, in gallery shows in Chelsea and beyond, and in the plethora of art fairs clinging like barnacles to the Armory Show on Pier 94 this weekend.

“Wack!” is a good place to trace a postracial impulse in art going back decades. Ms. Piper is one of the few African-American artists in the show, along with Howardena Pindell and Lorraine O’Grady. All three began their careers with abstract work, at one time the form of black art most acceptable to white institutions, but went on to address race aggressively.

In a 1980 performance video, “Free, White and 21,” Ms. Pindell wore whiteface to deliver a scathing rebuke of art-world racism. In the same year Ms. O’Grady introduced an alter ego named “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire” who, dressed in a beauty-queen gown sewn from white formal gloves, crashed museum openings to protest all-white shows. A few years later Ms. Piper, who is light skinned, began to selectively distribute a printed calling card at similar social events. It read:

Dear Friend,

I am black. I am sure you did not realize this when you made/laughed at/agreed with that racist remark. In the past I have attempted to alert white people to my racial identity in advance. Unfortunately, this invariably causes them to react to me as pushy, manipulative or socially inappropriate. Therefore, my policy is to assume that white people do not make these remarks, even when they believe there are not black people present, and to distribute this card when they do.

I regret any discomfort my presence is causing you, just as I am sure you regret the discomfort your racism is causing me.

Sincerely yours,

Adrian Margaret Smith Piper

Although these artists’ careers took dissimilar directions, in at least some of their work from the ’70s and ’80s they all approached race, whiteness as well as blackness, as a creative medium. Race is treated as a form of performance; an identity that could, within limits, be worn or put aside; and as a diagnostic tool to investigate social values and pathologies.

Ms. Piper’s take on race as a form of creative nonfiction has had a powerful influence on two generations of African-Americans who, like Mr. Obama, didn’t experience the civil rights movement firsthand, and who share a cosmopolitan attitude toward race. In 2001 that attitude found corner-turning expression in “Freestyle,” an exhibition organized at the Studio Museum in Harlem by its director, Thelma Golden.

When Ms. Golden and her friend the artist Glenn Ligon called the 28 young American artists “postblack,” it made news. It was a big moment. If she wasn’t the first to use the term, she was the first to apply it to a group of artists who, she wrote, were “adamant about not being labeled ‘black’ artists, though their work was steeped, in fact deeply interested, in redefining complex notions of blackness.”

The work ranged from mural-size images of police helicopters painted with hair pomade by Kori Newkirk, who lives in Los Angeles, to computer-assisted geometric abstract painting by the New York artist Louis Cameron. Mr, Newkirk’s work came with specific if indirect ethnic references; Mr. Cameron’s did not. Although “black” in the Studio Museum context, they would lose their racial associations in an ethnically neutral institution like the Museum of Modern Art.

Ethnically neutral? That’s just a code-term for white, the no-color, the everything-color. For whiteness is as much — or as little — a racial category as blackness, though it is rarely acknowledged as such wherever it is the dominant, default ethnicity. Whiteness is yet another part of the postracial story. Like blackness, it has become a complicated subject for art. And few have explored it more forcefully and intimately than Nayland Blake.

Mr. Blake, 48, is the child of a black father and a white mother. In various performance pieces since the 1990s he has dressed up as a giant rabbit, partly as a reference to Br’er Rabbit of Joel Chandler Harris’s Uncle Remus stories, a wily animal who speaks in Southern black dialect and who survives capture by moving fast and against expectations.

In 2001 Mr. Blake appeared in a video with another artist, AA Bronson. Each had his face slathered with cake frosting, chocolate in Mr. Blake’s case, vanilla in Mr. Bronson’s. When then two men exchanged a long kiss, the colors, and presumably the flavors, began to blend. Shared love, the implication was, dissolves distinctions between “black” and “white,” which, as racial categories, are cosmetic, superficial.

As categories they are also explosive. In 1984, when Mr. Hammons painted a poster of the Rev. Jesse Jackson as a blond, blue-eyed Caucasian and exhibited it outdoors in Washington, the piece was trashed by a group of African-American men. Mr, Hammons intended the portrait, “How Ya Like Me Now,” as a comment on the paltry white support for Mr. Jackson’s presidential bid that year. Those who attacked it assumed the image was intended as an insult to Mr. Jackson.

More recently, when Kara Walker cut out paper silhouettes of fantasy slave narratives, with characters — black and white alike — inflicting mutual violence, she attracted censure from some black artists. At least some of those objecting had personal roots in the civil rights years and an investment in art as a vehicle for racial pride, social protest and spiritual solace.

Ms. Walker, whose work skirts any such overt commitments, was accused of pandering to a white art market with an appetite for images of black abjection. She was called, in effect, a sellout to her race.

In a television interview a few weeks ago, before he formed plans to deliver his speech on race, Mr. Obama defended his practice of backing off from discussion of race in his campaign. He said it was no longer a useful subject in the national dialogue; we’re over it, or should be.

But in fact it can be extremely useful. There is no question that his public profile has been enhanced by his Philadelphia address, even if the political fallout in terms of votes has yet to be gauged.

Race can certainly be used to sell art too, and the results can be also be unpredictable. As with politics, timing is crucial.

In 1992 the white artist team Pruitt-Early (Rob Pruitt and Walter Early) presented a gallery exhibition called “The Red Black Green Red White and Blue Project.” Its theme was the marketing of African-American pop culture, with an installation of black-power posters, dashiki cloth and tapes of soul music bought in Harlem.

What might, at a later time or with different content, have been seen as a somewhat dated consumerist critique proved to be a public relations disaster. The artists were widely condemned as racist and all but disappeared from the art world.

Eight years later, with the cooling of identity politics, a show called “Hip-Hop Nation: Roots, Rhymes and Rage” arrived, with no apparent critical component, at the Brooklyn Museum of Art. An array of fashion images, videos and artifacts associated with stars like the Notorious B.I.G., Missy Elliott and Tupac Shakur, it was assumed to be a welcoming (if patronizing) gesture to the museum’s local African-American audience. Yet its appearance coincided with the general massive marketing of hip-hop culture to middle-class whites, a phenomenon that Mr. Pruitt and Mr. Early had been pointing to.

Were Pruitt-Early postblack artists ahead of their time, offering a new take on race, as a movable feast that collided with older, essentialist attitudes? If so, they would probably find plenty of company now in artists who stake out terrain both black and postblack, white and postwhite.

Mr. Pope.L (he who crawled up Broadway) does so with a posture of radical outsiderness that cancels bogus notions of racial or cultural essence. Basically he short-circuits the very concept of what an artist, black or white, “should” be. He smiles as he inches up the street on all fours; he uncomplainingly devours news of money he’ll never have. He paints murals with peanut butter and makes sculpture from Pop-Tarts, the stuff of welfare meals. In many ways his main subject would seem to be class, not race. Yet race is everywhere in his art.

He works with mostly white materials — mayonnaise, milk, flour — but he also runs the Black Factory, a mobile workshop-van equipped to transform any object, no matter what color, into a “black” object. How? By covering it with cheap black paint.

For a retrospective at the Maine College of Art in Portland in 2003, Mr. Pope.L presented a performance piece with the optimistic title “eRacism,” but that was entirely about race-based conflict. In a photograph in the show’s catalog, he has the word written in white on his bare black chest. Were he pale-skinned, it might have been all but invisible.

Whereas Mr. Pope.L has shaped himself into a distinctive racial presence, certain other artists of color are literally built from scratch. A Miami artists collective called BLCK, in the current Whitney Biennial, doesn’t really exist. The archival materials attributed to it documenting African American life in the 1960s is actually the creation of single artist: Adler Guerrier, who was born in Haiti in 1975.

Projects by Edgar Arceneaux, who is also in the biennial, have included imaginary visual jam sessions with the jazz visionary Sun Ra and the late Conceptual artist Sol Lewitt. Earlier in this art season, a white artist, Joe Scanlan, had a solo gallery show using the fictional persona of a black artist, Donelle Woolford. Ms. Woolford was awarded at least one appreciative review, suggesting that, in art at least, race can be independent of DNA.

The topic of race and blood has always been an inflammatory one in this country. Ms. Piper broached it in a 1988 video installation and delivered some bad news. Facing us through the camera, speaking with the soothing composure of a social worker or grief counselor, she said that, according to statistics, if we were white Americans, chances were very high that we carried at least some black blood. That was the legacy of slavery. She knew we would be upset. She was sorry. But was the truth. The piece was titled “Cornered.”

And are we upset? I’ll speak for myself; it’s not a question. Of course not. Which is a good thing, because the concept of race in America — the fraught fictions of whiteness and blackness— is not going away soon. It is still deep in our system. Whether it is or isn’t in our blood, it’s in our laws, our behavior, our institutions, our sensibilities, our dreams.

It’s also in our art, which, at its contrarian and ambiguous best, is always on the job, probing, resisting, questioning and traveling miles ahead down the road.

Wednesday, April 02, 2008

ok can i just say, e. badu "carries" fools like tavis smiley and they don't even know it.

goodness,

read on!

Erykah Badu

original airdate April 25, 2005

Erykah Badu has been called an uncompromising, brilliant artist. Growing up on '60s and '70s R&B, the Texas native wrote her first song at age 7. Her '97 debut CD, Baduizm, went platinum and won multiple awards. After some time out of the spotlight, Badu returned in '03 with Worldwide Underground. She's established a growing film career, with turns in Cider House Rules and House of D. Badu maintains strong ties to Dallas, TX with her nonprofit group B.L.I.N.D. (Beautiful Love Incorporated Non Profit Development).

TOPICS Music

Erykah Badu

Tavis: Erykah Badu is a four-time Grammy winner who burst onto the music scene back in 1997 with her terrific debut CD 'Baduizm.' Critics have praised her music for its unique combination of R&B, soul, jazz, and funk, but she's also a talented actress who won acclaim for a role you might recall in the Oscar-winning film 'The Cider House Rules.' Her latest movie is the David Duchovny-directed 'House of D.' The film is in theaters around the country even as we speak. Here now, a scene from 'House of D.'

Lady: And if you can walk, you can slow dance. Show me.

Tommy: No. Not out here in public.

Lady: I don't see no public.

Tommy: Well, come on. There's no music.

Lady: Imagine some music. You see that pole over there? That pole? Yes, that pole. Look at the pole. Walk toward the pole. You want this pole. No. Don't start your hands down at the ass. Work your way down.

Tavis: 'Look at the pole. Walk toward the pole. You want this pole.'

Erykah Badu: Right. You want the pole.

Tavis: You want this pole. Erykah Badu, nice to see you.

Badu: You, too.

Tavis: When David Duchovny was on this program a few weeks ago, he told me a funny story when the two of you were talking about the role for 'House of D.' He said you came in with a huge Afro. He was saying to you at the end of the conversation, 'Erykah, I like the look. If you could just keep that Afro until we shoot the movie, that'd be perfect, 'cause it fits perfectly for the role.'

Badu: Or he could keep it. Make sure it doesn't change.

Tavis: Make sure it doesn't change. He didn't know it wasn't real to begin with.

Badu: Uh-uh.

Tavis: Yeah. How do you decide what you're gonna do with your hair on a daily basis? All right? You got that, Jonathan?

Badu: How do I decide?

Tavis: How do you decide on a daily basis how you gonna rock this thing?

Badu: I don't give it a lot of thought, you know. It just--

Tavis: Are you trying to tell me there's no thought put into this?

Badu: No. It's just functional art, you know. It's just saying, well, you give thought to the tie.

Tavis: But I actually plan this stuff, though. I try to match the colors.

Badu: Did you lay it out on the bed... ...last night?

Tavis: You know what? Something like that. It wasn't last night. But this morning, yeah. I get up, try to match the color with the-- And you just do your thing.

Badu: Yeah.

Tavis: I like that, though. Functional art.

Badu: That's right.

Tavis: How much--on a serious note--how much of your hairstyle is part of your whole aesthetic, part of your image? How much does it play in, do you think? 'Cause everybody talks about it all the time.

Badu: I think the people would tell me that more than I can tell me that. Because I just come as me, which is a part of, you know, the art. So I think maybe it plays a big part, because it's a little to the left sometime, and eclectic, you know. I think it's maybe fascinating to some people. But you know...

Tavis: Yeah.

Badu: I don't know. You tell me.